Deer Biology

What is it about deer that makes them so attractive to watch but so damaging to people, property and wildlife habitat?

Can people safely and humanely fill the role of top predator to control their populations?

The answers to these questions depend in part on deer biology. Key facts about deer biology are reviewed below, followed by references that provide much more detail.

Diet

Deer are the largest herbivores (plant-eaters) in Virginia. They feed on grasses, herbaceous plants, leaves, twigs and buds during late spring and summer. They concentrate on berries, seeds, nuts, and acorns in the fall and early winter, and feed almost entirely on twigs and buds during late winter and early spring. A single adult deer consumes 5 to 7 lbs of plant matter in one day and over 1 ton in one year.

Suburban areas provide high-quality foods from gardens, landscape plantings, and fruit trees. At times of the year when natural food sources in woods and fields are depleted, such as the end of winter and during summer droughts, deer become especially bold in seeking food in developed landscapes such as residences and office parks.

Given a wide variety of plants to choose from, deer have definite preferences for high protein, tender, non-thorny plants. However, before a deer dies of starvation, it will eat virtually any type of vegetation.

Habitat

Deer inhabit deep forests, open fields, rocky mountain tops, coastal islands, and even cities and towns across Virginia. Deer can thrive anywhere just short of concrete and steel! Optimum deer country is a mixture of many habitat types (e.g., woods, fields, crops, brush, etc.) growing on fertile soils.

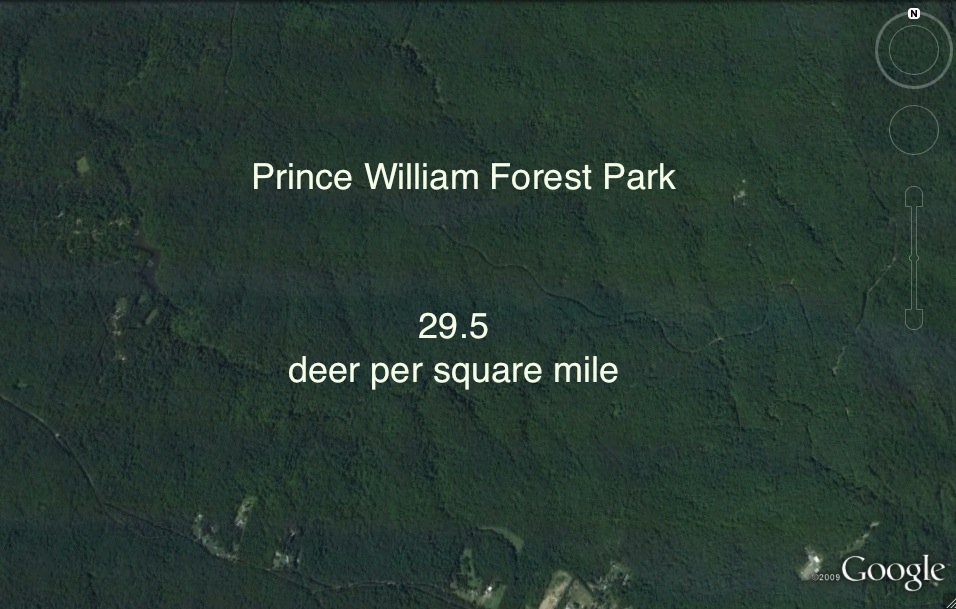

Deer are an “edge species” and use wooded areas for protective cover. The images below illustrate the importance of edge. Prince William Forest Park has the lowest deer density (eight year average, 2001 - 2008) and the least edge but plenty of cover. Manassas Battlefield Park has abundant edge and the highest density and sufficient edge for the highest density. Great Falls Park is intermediate in density even though there is little edge within the Park- but lots of edge on properties surrounding the Park.

Habitat for deer, like other wild animals, consists of four basic components:

- Food - an assortment of green plants, woody browse, mast (nuts and berries), and fungi

- Water – rarely a problem for a large, mobile animal;

- Cover (shelter) – almost any thicket, woodlot, hedgerow, or tall crop field;

- Space – bucks range over approximately 600 acres and does 200 acres in rural areas; 300 / 100 acres or less in suburban areas.

Behavior

Deer are naturally most active at dusk and dawn. Deer in suburban and urban areas may become active during mid-day when populations are high so they need to search more intensely for food. However, under heavy hunting pressure, they may alter their habits to become more nocturnal.

Deer herds are family groups primarily comprised of related female deer. Does leave the family group in advance of bearing fawns in spring. Yearling bucks may disperse from the mother’s home range when the mother abandons them in the spring or dominant bucks drive them away in the fall. Yearling does remain in the home range and rejoin the family group in early fall. Bucks are generally solitary but can form small bachelor herds when they drop antlers in the winter until they shed antler velvet and are ready to breed in the fall.

Deer become familiar with the area where they were born. This improves their chance of survival so they seldom leave their home range, especially the does. Bucks may expand their home ranges some during the breeding season but typically do not leave it. Due to this determined attachment to their home ranges, reducing deer numbers in one area will have little or no effect on populations just a few miles away. Thus, hunts in parks and other public properties may reduce deer damages on nearby private properties, but the effect is not widespread. Deer harvests must be conducted regularly in all deer habitats to manage them on a landscape or regional scale.

Deer movement increases dramatically during breeding season. Bucks are distracted when they are “in rut” and may travel outside their normal home ranges into unfamiliar territory. Does are chased around by bucks especially around the time they are in estrous. The increase in movements and the distractions of mating behaviors result in substantial increases in vehicle collisions during the fall.

Reproduction

Breeding season is October through January, with the peak of activity in November across much of Virginia. Gestation is approximately 28 weeks. Fawns are born April through July. Does typically produce a single fawn their first breeding season and produce 2 to 3 fawns each subsequent year in good habitat.

Deer populations can grow rapidly because does breed early (generally at 1 year-old), have twins most years, and continue to breed into old age (often 8-10 years). One buck can breed with many does, so removing bucks impacts populations little. Does control deer populations, so deer population management must focus on does.

Under optimum conditions, a deer population could double in size annually. With no regulating factor (e.g., predators, hunters, vehicles), a deer population would expand to the point where some resource, generally food, becomes scarce. Deer have few natural predators in Virginia, and other natural sources of mortality (e.g., diseases, injuries) are not sufficient to control populations.

How many fawns are born and how many survive each year depends in part on deer density relative to the food resources within the home range. As the figure to the left indicates, fawn recruitment increases with the number of deer (chiefly the number of does) until the maximum sustainable yield of the specific site is reached. Above that density, recruitment begins to drop as hungry does have fewer fawns and fawns can not find enough to eat.

Disease and Mortality

In general, deer can live eight to twelve years in the wild, but most do not live beyond four or five years due to predation, hunting and vehicle collisions.

Deer face little threat from natural large predators in Virginia although fawns are preyed on by coyotes, bobcats, black bears, and red foxes. Deer mortality is primarily a result of deer/vehicle collisions and hunting. In Fairfax County, collisions kill in the range of 2,000 to 5,000 deer per year, approximately two to four times as many as hunting, 1280 per year average from 2004 – 2009.

Surveillance for chronic wasting disease, bovine tuberculosis, hemorrhagic disease, and other health risks to Virginia’s wild deer population has become a high priority in recent years. Chronic wasting disease, an infectious, fatal brain disorder of deer, was discovered in a hunter-killed deer during 2009 in Frederick County, near an ongoing disease outbreak in West Virginia. High deer densities increase the risk of deer diseases due to more frequent contacts and to lower resistance if deer are so numerous as to be malnourished.

Deer Demography

Deer were plentiful and widespread when Europeans first settled Virginia in the early 1600s. By 1900, over-harvest of deer for food and hides had nearly extirpated the species. Since the 1930s, Virginia's deer population has rebounded as a result of protective game laws, restocking of deer into areas where they were absent, and habitat restoration. Since the early 1990s, deer management objectives have switched from restoring and increasing populations to controlling and stabilizing populations over much of the Commonwealth

The definitive description of how Virginia deer populations were nearly extirpated by 1900 and have recovered to be over-abundant in many parts of the state is published on pages 4 though 11 of the Virginia Deer Management Plan, 2006 – 2015.

Key References

See the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries web page for other information resources regarding deer and deer management.

Especially on the VDGIF site, see “Managing White-Tailed Deer in Suburban Environments – A Technical Guide”.

For in depth information about deer biology, see McShea, W. J., H. B. Underwood, and J. H. Rappole, editors. 1997. The Science of Overabundance – Deer Ecology and Population Management. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.